Chloe Thompson

Senior,

Spring 2016

Australian-born rapper Iggy Azalea has had hits, but her recent singles have failed to pack a punch. The rapper, who is of AngloIrish heritage,has several songs songs peppered with the catchphrase, “Tell me how you luv dat,” a line infamous for its use of monosyllabic, slang words, exemplifying the rapper’s frequent use of African American Vernacular English

(AAVE).

Azalea’s recent fall from fame illustrates the complexities of the Internet’s new attention to cultural appropriation — how it can glorify and redefine the adoption of cultural practices, and how cultural misappropriation can be fundamentally

detrimental to the reputation of its borrowers.

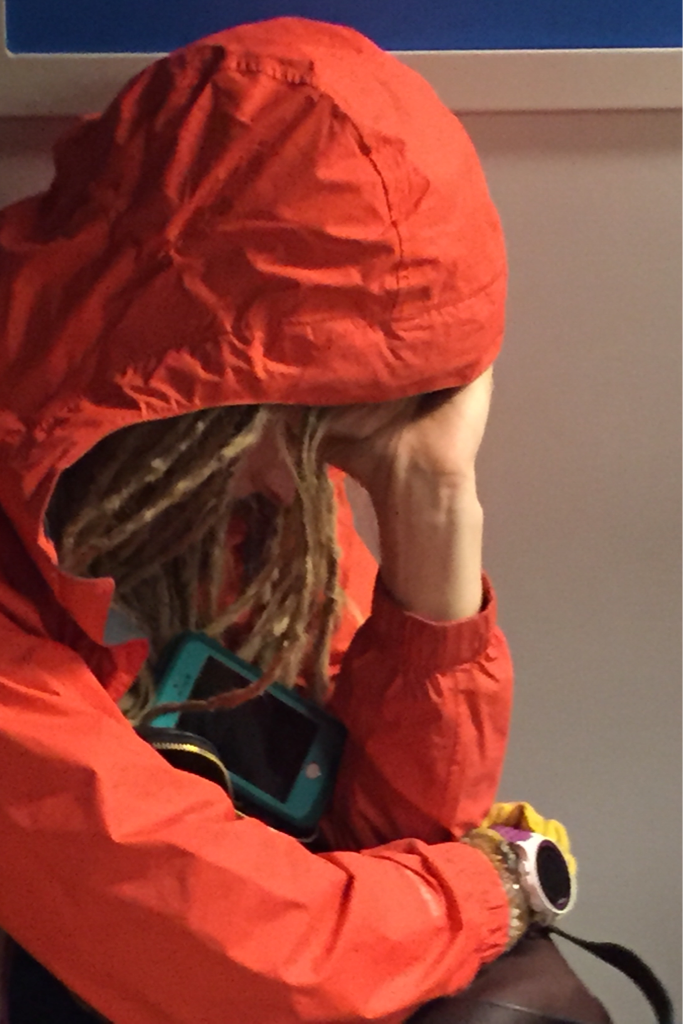

“When I had a dread in my hair, it was solely because it looked cool,” said MC Davis, a White high school senior. “I was never trying to degrade anyone’s culture. Then I got used to the idea of cultural appropriation, and took it out, even though my original intentions were never harmful.”

Cultural appropriation is a resurgent phase, sparking arguments on social media outlets over what’s considered appropriate or passé for different cultures to adopt from one another. It’s defined as “the adoption or use of elements of one culture by members of a different culture,” and was in previous years centralized to discourse regarding assimilation of Native American practices. In 2016, the discussion on cultural appropriation has taken on entirely new tones, focusing primarily on White American’s adoption of the cultural practices of different ethnicities for fashion-based purposes.

Internet personalities like Amandla Stenberg, actress from the Hunger Games, and Guardian columnist Jessica Valenti have frequently harped on the negative aspects of cultural appropriation. Both have noted that the fashions or vernacular language of appropriated cultures are looked down upon when done by the originators, but are revered when displayed by other cultures. In the spring of 2015, reality television star and social media maven Kylie Jenner was shot on the cover of Teen Vogue sporting brown faux dreadlocks, which captured the scorn of critics and Internet dwellers. Refinery29, a site

infamous for its exclusionary tactics regarding the glorification of white women in the arts, had columnist Erin Donnelly write,

“The problem here, of course, is the cultural appropriation involved. Dreadlocks are a traditional Black and Rastafarian style, one steeped in culture and racial identity.”

The issue with statements like the aforementioned is their lack of any kind of real explanation. Dreadlocks are a traditional Black and Rastafarian style, and they are steeped in culture and racial identity. The issue that stems from this defensive

comment is why it’s an issue for a young white woman to wear a hairstyle that is “steeped in culture and racial identity”.

While the images of preteen girls like Floridian Vanessa VanDyke being suspended for wearing an Afro, a hairstyle steeped in the same terms, comes to mind when thinking of the freeness Jenner had when sporting locks; the idea of being exclusionary seems congruent with telling young white women what they can and can’t do with their own hair. “To a degree, most things can be considered cultural appropriation,” said Sophia Giolitti, a high school senior. “The Social Justice Warrior stereotype does exist (in which) people obsessively defend what is and what isn’t appropriation. I do feel like it’s important to

think about how white people don’t have as many things that define them as a culture, which isn’t an excuse, but regardless of personal opinion, people are going to appropriate.”

Issues revolving around cultural appropriation regarding hair and fashion seem minute in comparison with issues like Iggy Azalea’s acquired AAVE, a warped way of speaking that the Australian rapper switches to on songs that is completely different from her normal, formal, accented speaking voice. Washington Post Journalist Jeff Guo wrote about the issue with

the “towering blonde spitting in unmistakably black tones”. The problem does not lay in Azalea’s choice of career as an artist in a majority black and male dominated industry, but in that Azalea feels as though she has to mimic the voices of the black and male to fit in, or possibly, to stand out.

As Guo states, “Azalea’s music attracts controversy because it doesn’t respect boundaries.” The rapper’s use of AAVE never feels complimentary, but instead, degrading, as though the only way rappers can become prolific is through one specific sounding voice. This form of cultural appropriation feels negative, but calls into question why it cannot follow the same path of the appropriation of fashion or hair, being easily simplified into freedoms, and because “everybody else does it”. Both of these issues exemplify how the complexities regarding cultural appropriation are innumerable, and seem unfix-able.

“Cultural appropriation is offensive to people, and I understand why.” said Brandon Shanahan, senior in high school. “I just don’t really see any way of it stopping (in addition to), the sharing of cultures leads to innovation, whether we dislike what we see right now on social media/in the culture or not.”

Cultural appropriation is an issue that will not leave the American conscience any time in the near future, regardless of individual opinions on what appropriation is, and how it should be defended. It seems as though the safest route to avoiding offensive appropriation is to not do it, but making decisions based on the defensive tactics of others prevents many from enjoying their own personal freedoms. As high school senior Maya MacDonald said, “I don’t think anyone should do it, but I can’t really stop them.”